Introduction to Mutual Information

In machine learning and data science tasks, measuring association between variables is an integral part of the modeling process. Traditional and perhaps naive techniques, such as the correlation coefficient, can fall short of identifying strong, non-linear relationships between variables. In this notebook, we introduce Mutual Information, which is a flexible and powerful measure of dependence possessing several desirable properties.

Entropy

Before we share the technical definition of mutual information, we will build up to it by first introducing a fundamental concept in information theory: Entropy. Let $X$ be a discrete random variable. The entropy of $X$ is defined as

\[H(X) = \sum_{x \in X} p(x) \log \frac{1}{p(x)} = -\sum_{x \in X} p(x) \log p(x)\]We provide two definitions because the left equation is more intuitive. We can think of entropy as measuring the average uncertainty, ‘shock’ factor or ‘surprise’ about the realizations of a random variable. Note that base of the log informs the unit of information measured. We will take the base of the logarithm to be 2, such that the units of information are in bits. For example, we can compare the entropy for a fair coin and a fair die. Let $X$ represent the coin and $Y$ represent the die.

\[H(X) = 0.5 \log(2) + 0.5 \log(2) = \log(2) = 1\] \[H(Y) = \frac{1}{6} \log(6) + ... + \frac{1}{6} \log(6) = \log(6) = 2.58\]Hence, the die, on average, has more entropy than the coin. This makes sense because with a coin, your level of ‘surprise’ is limited to heads and tails, but with the die you can be surprised in 6 different ways. Note that these are simple cases where each outcome is equally likely, and entropy does not neccesarily scale with the cardinality of the random variable. For example, take a weighted die where 6 has a 95% chance of coming up, and the others have 1% chance.

\[H(Y) = \frac{1}{6} \log(6) + ... + \frac{1}{6} \log(6) = \log(6) = 2.58\] \[H(Y_{weighted}) = -0.95 * \log(0.95) - 0.05 \log(0.05) = 0.2864\]Now the weighted die has lower entropy than the fair coin, meaning that it has less of a ‘shock’ factor than the fair coin. This makes sense because 6 comes up so frequently that, on average, we’re not all that surprised at the outcome of the die because we expect a 6 most of the time.

Conditional Entropy

Conditional entropy tells us the entropy of a random variable, given some knowledge about another random variable. In other words, what is the shock factor of $X$ when we know something about $Y$? If the shock factor of $X$ is still large after learning $Y$, that implies that $Y$ doesn’t really inform us about $X$. Consider the conditional entropy of a random variable with itself. How shocked would you be at the outcome of a die roll, if you already knew that it was a 6? You would hopefully not be shocked at all, so the conditional entropy would be 0. We can define conditional entropy as

\[H(Y | X) = -\sum_{x \in X, y \in Y} p(x, y) \log \frac{p(x, y)}{p(x)}\]Consider the realization of loss on a vehicle policy in one year to be either $1000 or $0. Further suppose that a policy holder either has good credit or bad credit. We can summarize the joint distribution of these random variables below

| Good | Bad | |

|---|---|---|

| $1000 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| $0 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

Hence, it is unlikely there will be a claim in one year, but if there is a claim, it is 9 times more likely that policy holder has bad credit. Let’s compute the conditional entropy of the loss (denote $Y$), given the state of the policy holder’s credit (denote $X$). First, we need to find our baseline information, which is just the entropy of $Y$, because $X$ and $Y$ are independent, then

\[H(Y|X) = H(Y)\]meaning that the state of credit doesn’t inform us at all about the realization of a loss.

\[H(Y) = - \left[0.1 * \log 0.1 + 0.9 * \log 0.9 \right] = 0.469\]Now we can find

| $$H(Y | X) = H(\text{loss} | \text{credit})$$. |

The conditional entropy of $Y$ given $X$ is almost half of the marginal entorpy of $Y$! This means that given some information about the policy holder’s credit, we’re given about half the information required to explain the realization of a loss, which is quite substantial! Now, what if the state of credit was equally informative of the outcome of the loss? What do you predict the conditional entropy to be? Preserving the same marginal probablities for the realization of a claim:

| Good | Bad | |

|---|---|---|

| $1000 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| $0 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

Our conditional entropy now is

\[H(Y | X) = - \left[0.05 * \log \frac{0.05}{0.5} + 0.45 * \log \frac{0.45}{0.5} + 0.05 * \log \frac{0.05}{0.5} + 0.45 * \log \frac{0.45}{0.5} \right] = 0.469\]Which is exactly the entropy of $Y$! This means that the policy holder’s credit doesn’t tell us anything about realizing a loss.

Some final notes:

If

\[H(Y|X) = 0\]then $Y$ is completely dependent on $X$

If $Y$ is completely independent of $X$,

\[H(Y|X) = H(Y)\]Mutual Information

Now, mutual information is a natural extension from the marginal and conditional entropies. Consider $X$ and $Y$ again. If we know the entropy of $X$ and we know the entropy of

\[X|Y\]then the remaining information is the entropy shared between $X$ and $Y$.

\[I(Y;X) = H(Y) - H(Y|X)\]Recalling our loss and credit example, let’s compute the mutual information between loss and credit:

| Good | Bad | |

|---|---|---|

| $1000 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| $0 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

This is easy since we already have the calculation from conditional entropy section:

\[I(Y;X) = H(Y) - H(Y|X) = 0.469 - 0.267 = 0.202\]As mentioned in the condtional entropy section, the mutual information between $X$ and $Y$ is nearly half of the entropy of $Y$, indicating a strong relationship between $X$ and $Y$. For completeness, let’s also compute the mutual information for the credit-agnostic case

| Good | Bad | |

|---|---|---|

| $1000 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| $0 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

The mutual information now is:

\[I(Y;X) = H(Y) - H(Y|X) = 0.469 - 0.469 = 0\]Hence, again, there is no information shared between the loss and the credit of the policy holder!

A few properties of mutual information

Other equivalent definitions of mutual information include:

- Continuous Random Variables

- Discrete Random Variables

Notice that the two definitions above take the shape of the Kullback-Leibler Divergence.

Nonnegativity

Mutual information is lower bounded by 0. Recall that if $X$ and $Y$ are completely independent, then the joint probability distribution is the product of the marginals. As can be directly observed in the definitions above, indepedent random variables yield a mutual information of 0.

Symmetry

\[I(X;Y) = I(Y;X)\]Non-standardized

Mutual Information between two variables can be arbitrarily large if the marginal entropies themselves are arbitrarily large, which could falsely suggest a strong relationship. In effort to standardize the mutual information, we can think of mutual information as an analogue to covariance. If the variances of $X$ and $Y$ are large, then the covariance will also be large, but that does not necessarily suggest a strong linear relationship because we have yet to scale the covariance by the marginal variances.

\[\frac{I(X;Y)}{\sqrt{H(X)H(Y)}}\]Why Mutual Information and Not Correlation?

Mutual information is a far more flexible metric for univariate screening than correlation. Mutual information can capture a strong correlation, while a correlation measure may miss a strong dependency between two variables. In other words, mutual information is necessary and sufficient, while correlation is only sufficient.

from itertools import combinations

import numpy as np

from sklearn.neighbors import NearestNeighbors, KDTree

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from functools import reduce

from scipy.special import digamma

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.feature_selection import mutual_info_regression

import seaborn as sns

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

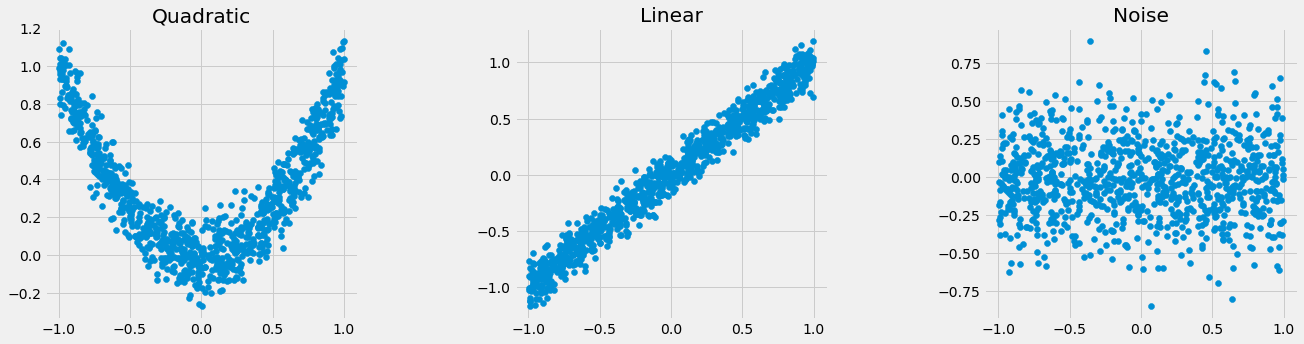

n = 1000

x = np.random.uniform(-1, 1, size = n)

y = x ** 2 + np.random.normal(scale = 0.1, size = n)

y2 = x + np.random.normal(scale = 0.1, size = n)

y3 = np.random.normal(scale = 0.25, size = n)

plt.figure(figsize = (20, 5))

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace = 0.4, wspace = 0.5)

plt.subplot(1, 3, 1)

plt.scatter(x, y)

plt.title('Quadratic')

plt.subplot(1, 3, 2)

plt.scatter(x, y2)

plt.title('Linear')

plt.subplot(1, 3, 3)

plt.scatter(x, y3)

plt.title('Noise')

plt.show()

Correlation

names = ['Quadratic', 'Linear', 'Noise']

for i, name in zip([y, y2, y3], names):

print(name + ": " + str(round(np.corrcoef(x, i)[0, 1], 3)))

Quadratic: -0.032

Linear: 0.985

Noise: -0.008

Mutual Information

for i, name in zip([y, y2, y3], names):

print(name + ": " + str(round(_compute_mi_cc(x, i), 3)))

Quadratic: 1.122

Linear: 1.67

Noise: 0

| Relationship | Correlation | Mutual Info |

|---|---|---|

| Quadratic | -0.032 | 1.122 |

| Linear | 0.985 | 1.67 |

| Noise | -0.008 | 0 |

If correlation were our only screening measure, we may have missed the quadratic relationship.

Estimating Mutual Information

Since we will likely never know the true, underlying probabilites distributions, we can’t compute mutual information analytically. Below we cover two methods for estimating mutual information.

Binning approach

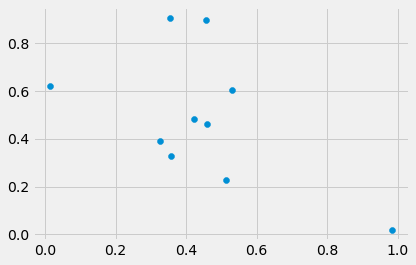

n = 10

np.random.seed(69420)

x = np.random.uniform(0, 1, size = n)

y = np.random.uniform(0, 1, size = n)

plt.scatter(x, y)

plt.show()

We can estimate the mutual information between $x$ and $y$ by making the follwing substitutions:

\[I(X;Y) = \int_y \int_x p_{X, Y}(x, y) \log \frac{p_{X, Y}(x, y)}{p_X(x)p_Y(y)}dxdy \approx I_{binned}(X;Y)= \sum_{i, j} p_(i, j) \log \frac{p_(i, j)}{p_X(i)p_Y(j)}\]where

-

$i, j$ are the respective bins of $X$ and $Y$

-

$p_(i) \approx \frac{n(i)}{N}$ is the fraction of the number of points in bin $i$ to the total number of points

-

$p_(j) \approx \frac{n(j)}{N}$ is the fraction of the number of points in bin $j$ to the total number of points

-

$p_(i, j) \approx \frac{n(i, j)}{N}$ is the fraction of the number of points in the intersection of bin $i$ and $j$ to the total number of points

a = np.round(np.column_stack((x, y)), 2)

a[a[:, 0].argsort()]

array([[0.01, 0.62],

[0.33, 0.39],

[0.35, 0.91],

[0.36, 0.33],

[0.42, 0.48],

[0.46, 0.9 ],

[0.46, 0.46],

[0.51, 0.23],

[0.53, 0.6 ],

[0.98, 0.02]])

If we pretend that the grid lines are our “bins”, then we can compute this mutual information. We have 10 points, and following the order in the array above we have:

\[I_{binned}(X;Y) = \\ \frac{1}{10} \log \frac{1/10}{(2/10)(1/10)} + \\ \frac{2}{10} \log \frac{2/10}{(3/10)(3/10)} + \\ \frac{1}{10} \log \frac{1/10}{(2/10)(3/10)} + \\ \frac{2}{10} \log \frac{2/10}{(3/10)(3/10)} + \\ \frac{2}{10} \log \frac{2/10}{(2/10)(5/10)} + \\ \frac{1}{10} \log \frac{1/10}{(2/10)(5/10)} + \\ \frac{2}{10} \log \frac{2/10}{(2/10)(5/10)} + \\ \frac{1}{10} \log \frac{1/10}{(3/10)(5/10)} + \\ \frac{1}{10} \log \frac{1/10}{(2/10)(5/10)} + \\ \frac{1}{10} \log \frac{1/10}{(1/10)(1/10)}\]This method should converge to $I(X;Y)$ as $N \rightarrow \infty$ and the bin widths go to 0, if the true densities are proper functions. This primer will focus on another method for estimating mutual information using a k-nearest neighbors approach.

$k$-nearest neighbors approach

A 2-Dimensional Estimator of Mutual Information

\[I(X, Y) = \psi(k) + \psi(N) - \langle \psi(n_{x_1 + 1}) + \psi(n_{y + 1})\rangle\]Suppose $Z = (X, Y)$

where

-

$\psi(x)$ is the digamma function

-

$k$ is the number of nearest neighbors

-

$m$ is the number of dimensions

-

$N$ is the number of samples

-

$n_{x_i}$ is the number of points $x_j$ strictly less than the radius, where the radius is the distance from $z_i$ to its $k^{th}$ neighbor.

The estimator can be found in the following paper: https://journals.aps.org/pre/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevE.69.066138. As shown in the paper, the authors propose an estimator from a nearest-neighbor approach which diverges from the traditional binning approach. They then briefly mention an extension for an M-dimensional estiamtor, which is given below.

Implementation

The code below modifies the source code from sklearn’s mutual_info_regression for a 2-dimensional estimator to correspond to the M-dimensional estimator given in the paper.

def _compute_mi_cc(x, y, n_neighbors = 3):

n_samples = x.size

x = x.reshape((-1, 1))

y = y.reshape((-1, 1))

xy = np.hstack((x, y))

# Here we rely on NearestNeighbors to select the fastest algorithm.

nn = NearestNeighbors(metric='chebyshev', n_neighbors=n_neighbors)

nn.fit(xy)

radius = nn.kneighbors()[0]

radius = np.nextafter(radius[:, -1], 0)

# KDTree is explicitly fit to allow for the querying of number of

# neighbors within a specified radius

kd = KDTree(x, metric='chebyshev')

nx = kd.query_radius(x, radius, count_only=True, return_distance=False)

nx = np.array(nx) - 1.0

kd = KDTree(y, metric='chebyshev')

ny = kd.query_radius(y, radius, count_only=True, return_distance=False)

ny = np.array(ny) - 1.0

mi = (digamma(n_samples) + digamma(n_neighbors) -

np.mean(digamma(nx + 1)) - np.mean(digamma(ny + 1)))

return max(0, mi)

An M-Dimensional Estimator of Mutual Information

We can modify the source code for mutual_info-regression such that we can take a $p$ dimensional design matrix and estimate the mutual information between $m$ predictors and the target.

Suppose $Z = (X_1, X_2,…,X_m)$

where

-

$\psi(x)$ is the digamma function

-

$k$ is the number of nearest neighbors

-

$m$ is the number of dimensions

-

$N$ is the number of samples

-

$n_{x_i}$ is the number of points $x_j$ strictly less than the radius, where the radius is the distance from $z_i$ to its $k^{th}$ neighbor.

Implementation

We can extend the above function with some slight modifications to account for m-dimensions.

def compute_mi_cc(X, y, N, n_neighbors):

m = X.shape[1]

Z = np.hstack((X, y))

### Instantiate the Nearest Neighbor model (note the chebyshev distance!!)

nn = NearestNeighbors(metric = 'chebyshev', n_neighbors = n_neighbors)

### Fit Z

nn.fit(Z)

### Find the distance to the k-nearest neighbor for each point in Z

radius = nn.kneighbors()[0]

radius = np.nextafter(radius[:, -1], 0)

### This will be a list of arrays that record the number of neighbors within each radius for each point for each X

neighbors = []

### Iterate through the columns of Z (which includes y!)

for i in range(Z.shape[1]):

### Reshape the array

Z_i = Z[ : , i].reshape((-1, 1))

### Instantiate the Tree (note the chebyshev distance!!)

kd = KDTree(Z_i, metric = 'chebyshev')

### Find number of neighbors within the radius

n_i = kd.query_radius(Z_i, radius, count_only = True, return_distance = False)

### Subtract 1 so as not count the point itself

neighbors.append(n_i - 1)

### Function for computing the mean of the digamma of the neighbors

digamma_mean = lambda x : np.mean(digamma(x + 1))

### Final Mutual Information Estimate

mi = digamma(n_neighbors) + m * digamma(N) - sum(list(map(digamma_mean, neighbors)))

### If the estimate is less than 0, just return 0

return max(0, mi)

The function below is just a wrapper for the above function.

def m_dim_mi(X, y, m = 2, n_neighbors = 3):

p = X.shape[1]

### Find all combinations of p of size m

all_pairs = list(combinations(range(p), m))

### Reshape y to two dimensions

y = y.reshape((-1, 1))

### Number of samples

N = y.size

### Compute Mutual Information Estimate for all pairs

mis = [compute_mi_cc(X[ : , pair], y, N, n_neighbors) for pair in all_pairs]

return mis

Application

One of the uses of mutual information is interaction detection. An (M - 1)-way interaction can be detected with M-way mutual information as we will illustrate below.

Data Generation

We will simulate some data in the following fashion, where two features interact.

Let \(X = (x_1, x_2, x_3)\)

where

\[X \sim U(-1, 1)\]and

\[Y = 10\exp \left(\frac{x_2}{2}\right) \cos(\pi x_1) + \epsilon\]where

\[\epsilon \sim N(0, 1)\]p = 3

n = 10000

X = np.random.uniform(-1, 1, size = (n, p))

y = 10 * np.exp(X[:, 1] / 2) * np.cos(X[:, 0] * np.pi) + np.random.normal(scale = 1, size = n)

Plot Data

df = pd.DataFrame(np.hstack((X, y.reshape((-1, 1)))))

df.columns = ['x' + str(i) for i in range(1, p + 1)] + ['y']

plt.figure(figsize = (20, 5))

for i in range(1, 4):

plt.subplot(1, 3, i)

sns.scatterplot(x = 'x' + str(i), y = 'y', data = df)

From the univariate plots, it appears that $x_2$ is not all that useful in predicting $y$.

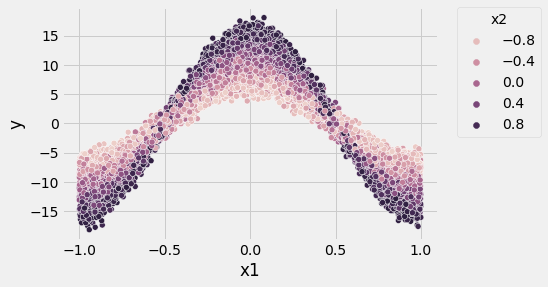

Visualize Interaction Effect

sns.scatterplot(x = 'x1', y = 'y', hue = 'x2', data = df)

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 1), loc='upper left', borderaxespad=0, title = 'x2')

plt.show()

Now it is clear that there is an interaction between $x_1$ and $x_2$. For example, take $x_1 = 0$. If we tried to predict $y$ with $x_1$ alone, we could be off by about 10 (refer to the univariate plot, at $x_1 = 0$, $y$ ranges from about 5 to 15), but if we then learned something about $x_2$, our error will shrink significantly (refer to the interaction plot and observe the distinct bands of $x_2$ with width of about 5).

Correlation

Let’s try to see if correlation can help us determine if there are any meaningful relationships.

df.corr()

| x1 | x2 | x3 | y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | 1.000000 | -0.009013 | 0.010549 | -0.013682 |

| x2 | -0.009013 | 1.000000 | 0.001111 | 0.004468 |

| x3 | 0.010549 | 0.001111 | 1.000000 | 0.013259 |

| y | -0.013682 | 0.004468 | 0.013259 | 1.000000 |

Clearly, correlation is not useful for these relationships.

Mutual Information between 2 variables

Now, we can try mutual information. We will compute the mutual information between each of the individual predictors and $y$.

X_new = df.copy()

y_new = X_new.pop('y')

discrete_features = X_new.dtypes == int

mi_scores = mutual_info_regression(X_new, y_new, discrete_features=discrete_features)

pd.Series(mi_scores, name="MI Scores", index=["MI between " + x + " and y: " for x in X_new.columns])

MI between x1 and y: 1.291825

MI between x2 and y: 0.293359

MI between x3 and y: 0.000000

Name: MI Scores, dtype: float64

Now, we are able see that $x_1$ is a strong predictor of $y$. However, if we stopped here, we might conclude that $x_2$ is not useful in the model.

Mutual Information between 3 variables

m = 2

mi_scores = m_dim_mi(X, y, m = m)

all_pairs = list(combinations(range(1, p + 1), m))

indices = ["MI between " + 'x' + str(pair[0]) + ' and x' + str(pair[1]) + " and y: " for pair in all_pairs]

pd.Series(mi_scores, name="MI Scores", index=indices)

MI between x1 and x2 and y: 1.783999

MI between x1 and x3 and y: 1.175598

MI between x2 and x3 and y: 0.282831

Name: MI Scores, dtype: float64

Finally, we see that there is a strong interaction between $x_1$ and $x_2$. Note that the mutual information with $x_3$ is very similar to the 2D mutual information for $x_1$ and $x_2$. This makes sense because $x_3$ is just noise and completely independent.